Avoiding The Pitfalls

Like most of us, your budget is limited when it comes to your hobbies, so this page is devoted to spotting potential problems before buying anything. If you'd like to get better at avoiding trouble by knowing what to look for, then scroll down.

The Buyer's Guide

Building Your Collection

Collecting antique watches is a fascinating hobby, not only for people that have an interest in the mechanical, but also for those who appreciate the history behind them. Prices can vary between a few hundred dollars and tens of thousands of dollars, so there's something for everyone. Most collectors want the very best examples they can find without over-spending, but even longtime enthusiasts sometimes buy a lemon. Here's some tips on how to avoid that:

Do Your Homework

The most successful collectors are the ones that do at least some research before buying anything. This means learning how many of a certain model were made, how long of a period in which they were made, which movement/case/dial combinations are correct, which variants are more desirable, and patiently checking current and past auctions to see what they bring.

When researching your watch always use multiple sources, because relatively few factory records remain after so many years and there are bound to be inaccuracies. Don't believe everything you read, and what really counts is the watch itself. Online databases that pose as a one-stop Mecca for those seeking a free instant education may be a good starting point, but they are certainly not the final word. The best sources of information are the surviving catalogs or supplements from the larger companies like Hamilton and Waltham, older books such as Michael Harrold's "Technical History of American Watchmaking", and individuals who focused on a single brand, such as Ron Prices's excellent work on Waltham's Model '57, Greg Frauenhoff's small publication on Aurora, Harold Visser's research on early Howards, Chris Bailey's book on Seth Thomas, and many others.

High-Grade Watches

Most people think that their watch is a railroad watch, but the requirements for railroad service were quite stringent, and the list of models that qualified was fairly small. Not every company made them, and the ones that did make them did not produce large quantities of them.

That being said, every novice collector and their brother wants a high-grade watch without knowing exactly why, convinced that more jewels somehow translates into higher accuracy. Because of this thinking and the relatively few survivors of high-grade pieces, these watches get passed around by collectors like a taco platter at a dorm party, with everybody's fingers in them. Low and mid-grade watches can be just as accurate as high-grade ones, since they all contain the same parts, and are often overlooked or disregarded, which is a mistake. An untouched 15-jewel watch in its original case is worth far more than a re-cased and thoroughly molested 21-jewel example with stripped screws and the wrong hands.

Condition, Condition

Watches in nearly-untouched condition are generally the most desirable, unless the piece is very rare from small runs of fewer than a hundred. Running watches are not always the ones to look for, and there are times when broken ones are the best choice. Why is that? Because the first owner may have dropped it eighty years ago, breaking the mainspring or the balance staff and simply tossed it in a drawer, where it's been ever since and now has almost no mileage on it.

There is a school of thought that mismatched hands and missing parts somehow form the tapestry of the watch, and that they should be left as a tribute to its service life. It's your collection and if you feel that way it's certainly your business, but mismatched hands are simply a testament to the laziness of someone who couldn't be bothered to find the right ones. The time will come to sell or auction your collection, and those in better shape will almost always bring higher prices.

"Serviced" Watches

There is a vast difference between professionally restored watches and those that have been simply dunked in cleaning solution or re-staffed using Superglue. Watches can take days to bring back to factory specifications, and anyone offering a complete "servicing" for $85 is obviously cutting corners. It takes well over a hundred close-tolerance parts working in unison for these antiques to function properly, and each and every one of them must be examined for fit and condition, and that includes the case pendant and the case itself. Examples with the regulator all the way to Fast or Slow while claiming to be serviced have likely never been touched.

The Bad Strategies

The worst thing you can do is chase the leftovers from any eBay parasites that part out original watches and sell the pieces, because you will absolutely pay more for the scattered parts than to simply buy the best example that you can afford. It's pointless to buy uncased movements since there are almost no decent gold-filled cases left, thanks to the relentless greed of the gold scrappers. Buying from flippers is relatively harmless, but the popular ones have many followers, so you're bidding against more people. There is a growing trend to "rescue" watches by buying a pile of parts big enough to hopefully assemble a running timepiece, and again you will absolutely pay more in the end than buying an intact and original example.

Originality and condition is highly prized in many of the things we collect, from baseball cards and coins to military accoutrements and celebrity memorabilia. These two aspects truly do matter, because if it weren't for originality and condition those items would be nearly worthless. The opposite is true for antique watches, where bizarre assortments of mismatched parts are wedged together in a gleeful show-and-tell in which the owner is actually proud of the mess that he just paid for - it's almost as if the stranger it looks, the better it is. There is also the "rat rod" approach, in which the movement keeps perfect time, while all three hands are wrong and the worn and dented case is deliberately kept as wretched-looking as possible. Auction houses, flippers, and bottom feeders have combined forces to ruin these once-magnificent works of mechanical genius.

The Good Strategies

A good place to find relatively unmolested watches are estate sales, garage sales, and small auction houses that don't specialize in such things. You may find interesting pieces at pawn shops and antique malls, but those places generally want ridiculous money simply because the watch is old. If you do troll eBay, look for sellers that don't routinely deal in antique watches because these are the attic finds, the safe-deposit box cleanouts, the inheritors that can't wait to cash in on Grandpa's watch, and the ones who don't know much about them. Joining closed groups on social media and buying from other collectors is a great idea, too.

The Best Strategies

Knowing exactly what to look for is the best way to avoid buying a Frankenwatch, a money pit, or a basket case. To do this you need to be able to spot issues before buying a pocket watch, so for anyone interested in learning the most obvious tip-offs, read on:

What To Avoid

On The Outside

Damaged Dials

Mismatched Hands

Mismatched Hands

Once a porcelain dial is broken or cracked it cannot be reversed, and replacements take time to locate. The damage usually occurs at the dial feet locations, the result of someone trying to pry the dial off before loosening the corresponding set screws.

Mismatched Hands

Mismatched Hands

Mismatched Hands

Incorrect or missing hands are an obvious problem because they can be difficult to find and expensive to replace, carefully fitted and installed parallel to the dial. The minute hand is more susceptible, since it's longer and sits the highest.

Visible Dents

Mismatched Hands

Visible Dents

Dents are always caused by an impact. The metal is now stretched, making it difficult to erase the worst dents. Additionally, the fall will likely have caused internal damage to the more delicate components, like the balance staff pivots and gear train jewels.

Bent Pendants

Missing Bezels

Visible Dents

A bent or leaning pendant is also the result of an impact. The stem inside the pendant will bind, making it more difficult to wind the watch. Any attempt to straighten a bent pendant carries the risk of breaking it off.

Blown Hinges

Missing Bezels

Missing Bezels

Hunter cases have delicate hinges and it doesn't take much to force the covers past 90 degrees. Once the metal of the frame is distorted it cannot be made right again. These are also called "sprung" hinges.

Missing Bezels

Missing Bezels

Missing Bezels

The bezel is the metal ring that holds the crystal, and is specific to that manufacturer and style of case. Finding a replacement can be nearly impossible with regard to metal color, and you still need a crystal.

Misaligned Patterns

Misaligned Patterns

Misaligned Patterns

Patterns on the case back that don't line up with the pendant were occasionally caused by a manufacturing defect, but the simple explanation is that the back is most likely from a different case, resulting in mismatched serial numbers.

Worn Parts

Misaligned Patterns

Misaligned Patterns

Bows wore out the quickest from the metal contact of chains, and crowns simply wore out from normal use, so yours could be the wrong style. Aftermarket replacements are available, though the color-match is seldom accurate.

Sidewinders

Misaligned Patterns

Sidewinders

Sidewinders are hunter movements in open-face cases. Seldom purchased this way historically, this arrangement means the original case has likely been melted down. Most collectors believe this configuration to be incorrect.

On The Inside

Molested Weights

Unoriginal Jewels

Unoriginal Jewels

A poised balance wheel is one that weighs the same at any point on the wheel rim, so any change in the weights will ruin its positional accuracy. This is one of the worst forms of intentional damage because the weights never need to be touched. When a watch slowed from thickening oils, the lazy choice was to grind off the weights to gain time.

Unoriginal Jewels

Unoriginal Jewels

Unoriginal Jewels

Obviously wrong jewels are another sign of damage. Milling a replacement jewel is an exact science with regard to pivot size, diameter, and shoulder thickness, although the new one may not be a perfect color-match. If the balance cap jewel sits too low it probably means that the balance was re-staffed with one that was too short.

Blown Jewels

Unoriginal Jewels

Ruined Hairsprings

Cracked or missing jewels also mean that the watch has been dropped, or worse, that someone separated the plates out of curiosity and then failed to align the pivots, shattering the jewels when screwing the plates back together. Jewels in gold settings are getting very hard to find, so replacements may not be a good color match.

Ruined Hairsprings

Ruined Hairsprings

Ruined Hairsprings

A hairspring is paired to the balance wheel in a process called vibrating, because there's a relationship between the length of the spring and the amount of mass on the balance wheel. Replacing the spring means adding or removing weight to re-poise the wheel and re-time the watch, which is time-consuming and costly.

Mismatched Screws

Ruined Hairsprings

Mismatched Screws

Incorrect or mismatched screws means that the original hit the floor and couldn't be found. Most American factories chose unique thread pitches to ensure that only their material was used, so an obviously wrong screw likely means that it came from a different brand with different threads, which are now stripped.

Broken Parts

Ruined Hairsprings

Mismatched Screws

Broken or missing parts may be difficult to replace, especially if the watch is a rare variant or the factory had a short run. It's common to find certain parts broken, such as lever springs, since not all designs were good ones and the part failed because of this. Others were simply discarded, like stopworks and regulator springs.

Rust and Corrosion

Half-Headed Case Screws

Half-Headed Case Screws

Wartime material shortages meant using acrylic (plastic) for crystals, which yellowed and trapped moisture, causing the hands to rust. If your piece has a glass crystal and the hands are still rusted, then the watch was probably stored for years in a damp location, which means that most of the internal steel components will have nascent corrosion.

Half-Headed Case Screws

Half-Headed Case Screws

Half-Headed Case Screws

Case screws with partial heads made it easier to mount the movement because they could be pre-loaded, but full-headed screws had to be threaded in later. The problem with half-headed screws is that the leading edge acts as a drill flute, eventually grinding their way completely through the case rim, leaving no metal, so the only option is an ugly washer.

Ghost Marks

Half-Headed Case Screws

Ghost Marks

Ghost marks are ugly scrapes caused by case screws from other movements, meaning that the one in the case is not the original. While this is not critical, original combinations are generally worth more. After repeated swaps a movement may end up in a replacement case that's a poor fit, or has incorrect stem depth, misaligned lever cutout and more.

Key Winds

Condition and Wear

These pieces represent the origins of the American watchmaking industry, and so are decades older than railroad-era watches. This means they've had decades more of hobbyists and tinkerers doing "repairs" and altering them in sometimes-permanent ways.

Stripped screws are by far the most common issue, with the factory threads ruined and holes reamed out. Mismatched hands, broken jewels, and blown-out taper pins on dial feet are very common, as are weak case hinges and lids that won't stay closed.

Quality and Tolerances

The earliest examples had solid balance wheels, flat hairsprings, press-fit jewels, concealed banking pins, and other designs that made them less than accurate and tough to service. The hairspring was under the balance wheel, making it difficult to put in beat, and the jewel/bushing locations could vary considerably so that the gears were not always perpendicular or even spaced correctly.

Swiss Knock-offs

The Fakes

Not to be confused with genuine Swiss companies like Bulova or Longines, Swiss look-alikes were produced to resemble American originals, usually with familiar-sounding names like Franklin but with a letter or two transposed to avoid legal problems. It's difficult to describe just how cheap and poorly-made these pieces are.

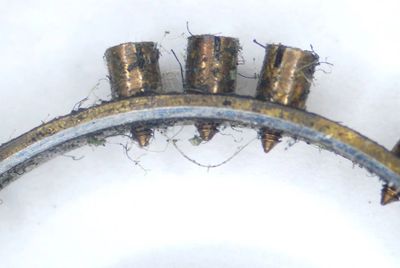

This particular example even has non-functional crown and ratchet wheels to mimic American brands, though the ratchet wheel on this one is missing (red circle). Note that the jewel setting screws (red arrow) are not actually mounting the jewels, but just sitting there next to them on the plate.

The Choo-Choo

Many generic Swiss factories (today we would say Made In Taiwan), tried to market these cheap watches toward our American railroad industry by adding names of familiar rail lines and images of trains on both the dial and the movement plates.

They are the lowest of the low. They have poor tolerances, soft alloys, coarse threads, fake jewels, and are not even close to railroad grade.

This example is a clear mimic of an American Model 2 Hampden.

Drops and Impacts

The Number One Clue

People have been dropping their watches for centuries, because that's what people do. The damage can range from a little to a lot, but how do you know if a watch has been dropped?

Other than dents, which aren't always obvious because they could be in the frame, the single biggest tip-off to a drop is a plastic crystal. When someone dropped their watch it almost always broke the glass crystal, and for some reason they usually went with a cheap plastic replacement that yellowed and caused the hands to rust, like this 16-size Hampden.

Mismatched Balance Jewels

Assuming that you can get the back off, another big clue is an obviously mismatched balance cap jewel that doesn't look like the other jewels.

One of the first things to break on a watch because of an impact is the balance staff and the four jewels in which it rotates. The brass cap jewel in this photo is in itself not a big problem, but it's a clue, since anyone lazy enough to use a brass jewel instead of a gold one to match the other plate jewels will usually take shortcuts elsewhere.

Want to know what those shortcuts are? Then read on.

Breaking the Jewels

Breaking the Jewels

Breaking the Jewels

When a watch falls, one or both balance pivots will likely break. The first one that breaks will allow the balance wheel to twist, and the leverage placed onto the pivot at the opposite end is enough to shatter the brittle hole jewel.

Breaking the Staff

Breaking the Jewels

Breaking the Jewels

Why does the balance staff always suffer? It's simple - the ratio of the mass of the balance wheel to its pivot size is the highest of any component within the gear train, so if the watch falls then one or both balance pivots will very likely bend or break off.

The Wrong Size

Breaking the Jewels

The Wrong Staff - Upper

When a staff breaks, a tinkerer will usually buy a single staff off eBay, but that person won't bother to measure it for any of its seven dimensions, convinced that all balance staffs are the same size and that the eBay seller sold them the right thing.

The Wrong Staff - Upper

The Wrong Staff - Upper

The Wrong Staff - Upper

If the replacement staff is wrong then the balance wheel could sit too high, rubbing against the underside of the balance cock or the regulator arm. In this photograph the tinkerer filed down the regulator arm in an attempt to make room for the wheel.

The Wrong Staff - Lower

The Wrong Staff - Upper

The Wrong Staff - Lower

If the replacement staff is wrong then the balance wheel could sit too low, slowly grinding a mark into the upper plate and permanently scarring it. In this photo the tinkerer never bothered to check if the wheel was clearing the plate.

Gluing the Staff

The Wrong Staff - Upper

The Wrong Staff - Lower

If he locates the right balance staff and doesn't own a decent staking set, our tinkerer will try to install it by gluing everything together - the staff, the wheel, the roller table, and roller jewel. Cyanoacrylate (Superglue) makes a brittle bond and will eventually fail.

Factory Original

Unfinished Rivets

Unfinished Rivets

If the balance staff is original, the rivet that holds it to the wheel will be finished flush like in the above photo, and all of the staff's dimensions will be correct with regard to overall length, balance seat, hub height, hairspring and roller seat, and pivot size.

Unfinished Rivets

Unfinished Rivets

Unfinished Rivets

If our tinkerer has a quality staking set he will try to rivet the new staff to the balance wheel. Assuming that the fit is correct, the rivet still must be dressed by milling it flat and flush with the balance arms. In this photograph that clearly was not done.

Broken Rivets

Unfinished Rivets

Broken Rivets

If the balance seat diameter is too small, the tinkerer will simply hammer away at it until the metal spreads enough to trap the wheel. This will cause the rivet to crack and weaken, and the staff won't center itself in the arbor hole, so the wheel will wobble.

Loose Rivets

A successful rivet is a tight, clean, centered rivet - one that securely mounts the balance wheel in both the flat and the round.

The re-staff attempt in this video is obviously a complete fail, leaving the wheel itself loose and free to rotate easily.

Ruining the Balance Wheel

Ruining the Balance Wheel

Ruining the Balance Wheel

Some tinkerers will heat the broken staff to soften the metal before punching it out. Of course, all this does is overheat the balance wheel and hairspring, removing the temper from anything made of steel. The hairspring in this photo is ruined.

Donor Balance Wheels

Ruining the Balance Wheel

Ruining the Balance Wheel

If our tinkerer ruins the existing wheel by making the arbor hole oval and ragged, he could use a wheel from a different watch and just scratch out the serial number. The donor wheel won't have the same mass as the old one, and the accuracy will suffer.

Breaking the Collet

Ruining the Balance Wheel

Breaking the Roller Table

If the hairspring seat on the replacement staff is too large then the collet will break when our tinkerer gleefully pounds it back on. This is by far the single dumbest, most expensive mistake of all because replacing a collet is both time-consuming and costly.

Breaking the Roller Table

Not Seating the Roller Table

Breaking the Roller Table

The same goes for the upper roller table and the lower table and the spacer if the staff is double-roller. If the dimensions of the replacement staff are too large, then the table will break as the tinkerer is happily pounding it on with his mighty hammer.

Gluing the Roller Table

Not Seating the Roller Table

Not Seating the Roller Table

If our tinkerer breaks the roller table he might use Superglue or epoxy to try to glue it back on. Again, this is a very poor bond and will eventually fail, allowing the parts to fall off into the gear train, which is just what happened in this photograph.

Not Seating the Roller Table

Not Seating the Roller Table

Not Seating the Roller Table

If our tinkerer is really dazed he'll fail to fully seat the roller table and not bother to check under the stereoscope. If the roller table is sitting too low it will hit the pallet arm and if the roller jewel is sitting too low it will strike the plate, stalling the watch.

Tinkerers and Parasites

The worst thing that can happen to a vintage watch is a tinkerer. They usually get their training by watching a few YouTube videos and then diving right in with pliers and Superglue, their favorite tools. They strip threads, lose or discard parts, grind down balance weights, break springs, crack collets, smash jewels, force in wrong screws, fail to measure anything, and make a hell of a mess installing undersized crystals with too much glue. They swap cases at random regardless of vintage, deliberately install mismatched hands, cut the dial feet off and then use carpet tape to stick the dial to the pillar plate. Yes, it's their watch and they can do whatever they like, but knowing when you're in over your head can mean the difference between ruining a rare piece or backing away and saving one. If the quality of the work is adequate then there's no problem, but understand that the overwhelming amount of intentional damage done to these antiques is caused by tinkerers.

Enjoy these two galleries of "repairs" performed by tinkerers sweating over their kitchen table:

The Fixes

Superglue Fails

The Parasites

As if tinkerers weren't bad enough, there are several kinds of self-styled middlemen who contribute nothing to the hobby or the study of horology. They don't repair, collect or research, but instead part out these antiques piece by piece and usually melt down the gold case.

The launching of eBay provided the perfect marketing platform for a few greedy individuals to resell the thousands of pocket watches that they've ruined so far. Where did they get the money to buy so many of them? From the revenue stream provided by anyone who bought their leftovers.

And here they are:

The Flippers

This clever bunch outbids all others to win a watch at auction, and then will promptly re-list the same watch to the same audience at a higher price. There is absolutely no skill involved in this relatively harmless practice, unless you like paying more than necessary.

The Gold Hogs

Solid gold and gold-filled cases have all but disappeared, thanks to the relentless greed of both the scrappers and the auction houses that sell to them. Gold hogs purchase vintage watches with the sole intention of melting down the cases, which obviously can't be replaced.

The Scrappers

In several ways, these unskilled jerks are the worst. These gleefully destructive slobs disassemble intact and original combinations and sell the individual parts for profit, while the NAWCC looks the other way. Professional auction houses are often their biggest suppliers, who know exactly what their intentions are. Novices swarm to buy their ruined leftovers, lured in by over-hyped ads with hysterical catchphrases, hoping for a bargain and completely ignoring whether a given dial or set of hands is correct for a particular movement, and then discover just how expensive it is to reassemble the scattered pieces. There are very few original watches left, thanks to this flea-market approach to collecting.

Want to know who they are, their eBay handles, and their real names?

Watch Lanyards

Tired of your watch smashing to the floor and having to pay all those irritating repair bills?