All About Dials

The dial was the most visible part of a watch, coming in an incredible array of styles, fonts and colors on substrates from metal to porcelain to celluloid. Learn the basics of dial construction and the types of materials used, see the different layouts, and enjoy a section devoted to fancy dials and private labels.

Porcelain Enamel Dials

A porcelain-enamel (glass) dial started as a round copper disc before the holes were drilled, any cutouts made, or the feet attached. Sintered porcelain was then powdered onto the top and fired in a kiln until the porcelain flowed like wax. The characters and signatures were all added later by teenage girls, who had the smallest hands.

Pressed

Single-Sunk

Single-Sunk

This was the simplest design, made from a copper disc with stamped depressions to create the lower level for the seconds hand, and used primarily on lower-grade pieces.

Single-Sunk

Single-Sunk

Single-Sunk

Single-sunk (or sunk) dials had a separate seconds bit that was soldered to the main dial. This was done so that the seconds hand could sit lower, allowing the hour hand to clear it.

Double-Sunk

Single-Sunk

Double-Sunk

Double-sunk dials were assembled from three separate pieces of different thicknesses, and were generally used on higher-grade watches. Triple-sunk dials were used on indicators.

Blind Man

Montgomery

Double-Sunk

Most watch companies made a very simple dial with bold Arabic numerals called the Blindman's Dial in response to stricter railroad standards in the 1890s. There were no distractions on it such as different colors or additional numbers, making it easier to tell the time at a glance and reducing the chances of misreading the position of the hands.

Montgomery

Montgomery

Montgomery

Henry Montgomery was granted a patent for a design that he called the Safety Dial while he was Inspector for the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway from 1896 to 1923. It had marginal minute numbers that were all upright (not radial like other dials), red five minute subs between the other minute markers, and a '6' inside the seconds bit.

24-Hour

Montgomery

Montgomery

The 24-hour dials were a requirement for the Canadian railways, which became standard in the mid 1880s. The 13 to 24-hour Arabic markers were generally inside of the 12-hour ring, and there were many variations. Dials with combinations of Roman and Arabic characters together were common and could also be found in Montgomery styles.

Wind-Indicator

Moorhouse and O'Hara

Moorhouse and O'Hara

Elgin, Rockford, and Waltham were the only American factories that made pocket watch wind-indicators in quantity. When the watch is fully wound the indicator hand is starting at zero, marking the passing of the hours as the mainspring unspools. Note the word "Wind" where the 24-hour marker would be is placed as a reminder.

Moorhouse and O'Hara

Moorhouse and O'Hara

Moorhouse and O'Hara

Josiah Moorhouse emigrated to America in 1854, eventually finding work as a dial painter by Nashua and Waltham while inventing his own distinctive style. Daniel O'Hara first worked for Waltham making watch cases, pairing with Edwin Weatherbee around 1890 in what would become the O'Hara Dial Co, makers of colored watch dials.

Ferguson

Moorhouse and O'Hara

Hand Painted

Louis Ferguson of Louisiana applied for a patent on his design in November of 1907, which was granted a year later. He produced porcelain dials for many local factories, and they are valuable, so check the back of the dial for the appropriate patent stamps. Hands were originally supplied with the dial and color-matched with the numerals.

Hand Painted

Characters and Numerals

Hand Painted

Before templates and uniform stamps became the norm, dials were painted by hand and then sealed under the final top glaze. This allowed for literally anything that the artist could imagine to be created, which usually meant bucolic scenes with many colors and themes. Most art of this kind was found on fusees before the advent of factories.

Characters and Numerals

Characters and Numerals

Characters and Numerals

Every imaginable theme could be found on watch dials, from logos for organizations and clubs to a myriad of sports and even erotica. The numerals could be Roman or Arabic, or they could be signs, symbols or letters spelling out the name of the owner. This dial is known as a Saracen dial, complete with camels and pyramids, made by Elgin.

Photo Transfers

Characters and Numerals

Characters and Numerals

Someone very clever figured out a way to use watch dials as glass negatives when shooting with a box camera, which also meant that the first examples were mirror images. Portraits were a common theme, though other images were occasionally worthy of attention, such as the colored nudes on this Model '83 Waltham.

Composite Dials

Celluloid

Aftermarket

Melamine

Celluloid was a perfect medium for the film industry, though it was used for dials by a few watch companies. Invented in the 1860s, it was one of the very first thermoplastics, a polymer based on camphor, a natural form of wax harvested from evergreen trees.

Melamine

Aftermarket

Melamine

Melamine was an early laminate made with formaldehyde, arising from war-time material shortages during World War II and used in place of enamel. Melamine dials have a flat, dull look and surface cracks that will only worsen as they age and deteriorate.

Aftermarket

Aftermarket

Aftermarket

Aftermarket dials are post-WW II items on metal plates that were meant to replace damaged originals, made by Swiss firms like LaRose. The tip-offs are 5-minute markings that are too cherry-red, and sinks with incorrect diameters and indistinct edges.

Metallic Dials

Patterned

Patterned

Patterned

Patterned metal dials were painted or milled, and some were considered railroad grade as Hi-Visibility. Scenic settings, milled patterns, and the fact that they can't crack are some of the benefits.

Secometer

Patterned

Patterned

Metal dials made punch-outs possible for rotating seconds sub-dials under the main one, which were called secometers, an early form of digital display. Several firms like Waltham and Illinois made them.

Embossed

Patterned

Embossed

These are similar to patterned dials, except the patterns were raised, making them useful as a Braille dial. They were more popular in Europe, and relatively few American factories produced them.

Art-Deco

Patterned

Embossed

As watch patterns became more plain, the emphasis shifted to the dial in the 1920s. Patterns and raised numerals became common, and different fonts and multiple colors all emerged.

Center Speckled

Center Speckled

Center Speckled

These dials were very striking, with a standard white outer chapter for visibility around a gold-foil center sink. This was an ideal design to dress up what would have been a plain dial without losing function.

Black and Gold

Center Speckled

Center Speckled

Another version of the center speckled dial, but with a black outer chapter and a textured inner sink. Gilt characters, numerals, train tracks, and minute markers make this a very elegant look.

Raised Numeral

Center Speckled

Raised Numeral

A somewhat plain dial on a white painted background, but with gilt numerals that were well proud of the surface, which provided a dozen numbers for the hands to snag on and stall the watch.

Pinstripes

Center Speckled

Raised Numeral

Metal dials with pinstripes were fairly rare, because it meant interrupting the pattern to place sixty dots as minute markers before the addition of the raised gold numerals and the brushed center sink.

Skeletonized

Sunburst/Rayed

Skeletonized

Dials with most of the center chapter deliberately removed for increased visibility of the inner workings of the gear train were called skeletonized, and were offered as novelties by factories like NY Standard.

Military

Sunburst/Rayed

Skeletonized

Military dials from WWII had white characters painted onto a black background for clarity. Earlier versions used radium, a radioactive-decay isotope that glowed on the characters, the hands, and the numbers.

Sunburst/Rayed

Sunburst/Rayed

Sunburst/Rayed

A rayed patterned, so named for the rays of light from the sun, was made with a rose engine, which was a rotary tool that could cut repeating lines while expanding outward or shrinking inward.

Painted

Sunburst/Rayed

Sunburst/Rayed

Factories did offer painted flat dials, though usually in gray or one of the earth tones like tan. They never really caught on in the 16 and 18-size pieces, but were very popular on the 12-size dress watches.

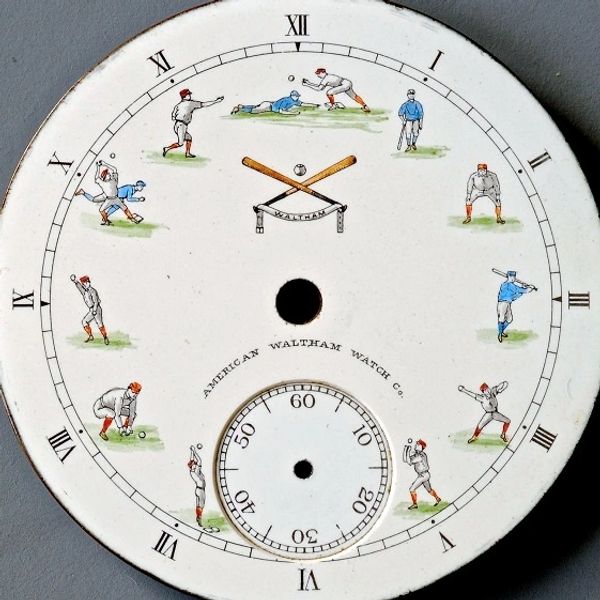

Fancy Dials

Fancy dials were also made from kiln-fired porcelain. Each additional color meant another trip through the kiln, which made them even more brittle and more delicate. Depending on the brand, they are scarce to begin with and any undamaged examples are worth collecting.

Conversion Dials

Conversion dials allowed hunter movements to be oriented as open-face by relocating the seconds bit to the 3:00 position, returning the winding stem to 12:00. These began showing up after WWI, were usually made of metal, and could be railroad acceptable. They could also be found in a reverse configuration, making a left-handed sidewinder.

Private Label Dials

Private label watches were those with the name of a person, a group or club, or a local jeweler inscribed on either the dial, the movement or both. Orders were placed through regional jobbers, who acted as distributors for the factory.

Fake Dials

Identifying fakes is not always easy, but there are usually several obvious tip-offs, such as ragged edges, red numerals that are too vivid, fonts that seem oddly modern, sink edges that are somewhat ragged, spacing between characters, and an overall crudeness that the eyes pick up without realizing it.

A Fake Hamilton Dial

Cherry-red subs, wrong numeral font, arrows and not dots, seconds sink diameter too large, and the seconds arbor piercing the '6'.

The Real Thing

Slightly faded red subs, an elegant numeral font, dots and not arrows, the seconds markers matching the sink diameter, and the '6' intact.

Mounting the Dial

Pinned Dials

Watch dials were first held in place by brass taper pins piercing the copper feet on the back of the dial. They were a poor design choice, with the pins constantly getting lost and sometimes falling into the movement. The holes in the dial feet would become enlarged, making removal and installation difficult, leading to cracks and other damage.

Set Screws

Taper pins gave way to to the much more practical method of securing the dial with set screws (red arrow). The larger dial sizes had two, three and even four feet, and their location was not standard, varying on every model, and every factory made screws with different threads.

Dial Damage

Missing chunks of porcelain or hairline cracks are not due to age, but the result of some fool trying to pry off the dial without loosening the set screws first. This is an obvious sign of a tinkerer.

Threaded Feet

A few companies mounted the dial with screws passing through the movement (E Howard was one), threading them into pockets on the dial back, but these are exceedingly rare because of the possibility of someone over-tightening the screws and cracking the dial.

Snap-On Dials

Smaller-size watches generally had snap-on dials to save room on the pillar plate, although a few larger models used them too. Since the only way to remove them was to pry them off, cracked and broken examples are all too common.

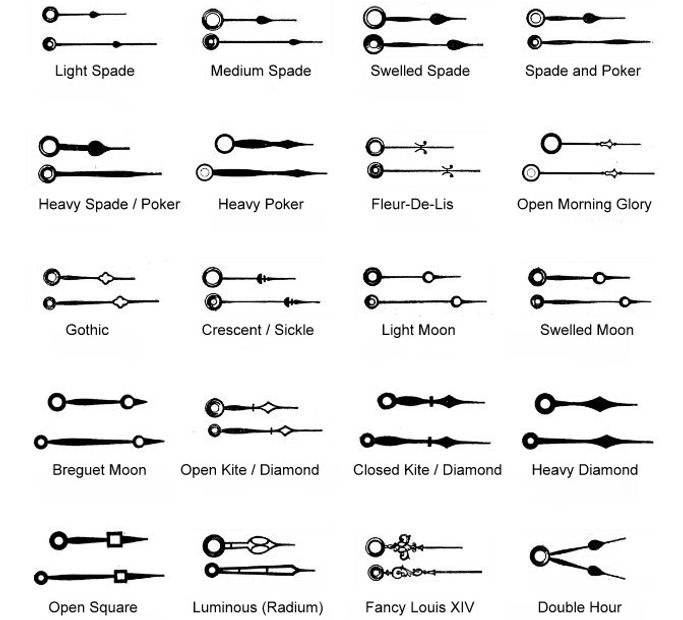

Watch Hands

The Styles

Dials weren't much use without hands, and they came in many different styles and colors.

The factories were able to stamp these delicate steel parts with great precision, especially the pierced ones with tiny irregular holes. Bluing (tempering) took place in basement kilns, to harden them and also to impart the colors of plum and cobalt blue. Painted hands were scarce and black would come later, but nearly every company offered fancy gilt hands.

The Colors

Cobalt Blue

Cobalt Blue

Cobalt Blue

By far the most common, achieved by heating the steel hands to 450° F.

Plum

Cobalt Blue

Cobalt Blue

Used primarily by Illinois, done by heating the steel hands to 400° F.

Black

Cobalt Blue

Black

Hamilton used black on later models, made by quenching the hot steel in oil.

White

Multi-Colored

Black

Black dials were for military service, using painted white hands for contrast.

Multi-Colored

Multi-Colored

Multi-Colored

Ferguson used the dial and hands as a system with matching the colors.

Gilt

Multi-Colored

Multi-Colored

Fancy hands, commonly called Louis XIV, were produced by gilding soft brass.