Watches Advanced

How does the balance wheel affect accuracy? What were stopworks used for? Where are the meantime screws?

Learn the basics of watch mechanics, some of the internal components, railroad standards, movement sizes, types of escapements, numbers of adjustments, plate finishes and more.

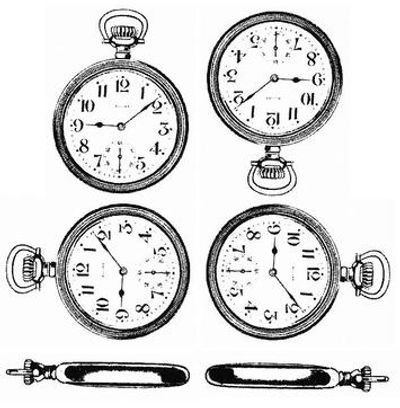

How A Watch Works

What Makes It Run

Watch this short video to see how the mainspring torque pushes through the gear train and the lever escapement to impel the balance wheel to oscillate. The design of the watch in this video is typical of nearly all American models during the railroad era, containing a mainspring, three-wheel gear train, anchor or lever escapement, and balance wheel assembly.

The Components

These are the primary components in most American pocket watches, though the visual layout may change between models:

The Mainspring

- Click - prevents the mainspring from unspooling

- Barrel Cover - traps the mainspring

- Mainspring - stores power to drive the gear train

- Mainspring Barrel - holds the mainspring and meshes with the center wheel

- Ratchet Wheel - meshes with the crown wheel and winds up the mainspring

- Mainspring Arbor - mounts the ratchet wheel and hooks the spooled mainspring

- Crown Wheel - transfers power from the winding stem to the ratchet wheel

The Gear Train

- Third Wheel - meshes with the center and 4th wheels

- Fourth Wheel - meshes with the 3rd and escape wheels

- Fourth Wheel Pinion - mounts the seconds hand

- Center Wheel - meshes with the barrel and 3rd wheel

- Safety Pinion - uncouples if the mainspring breaks

- Center Wheel Pinion - mounts the canon pinion, which mounts and drives the hour and minute hands

The Gear Train Speeds

Slow Train

The earliest American watches ran on a "coarse" gear train, designed for precisely 4.5 beats-per-second (BPS). Multiplying 4.5 BPS by 3,600 seconds in an hour returns 16,200 beats-per-hour.

Quick Train

In later years the balance rate would rise to 18,000 BPH to increase accuracy. That figure translates to 432,000 beats per day, 3,024,000 per week, 12,960,000 per month, and 157,680,000 per year.

English Train

With the advent of the lever escapement, English watchmakers chose 14,400 BPH (4 BPS) as their train speed, which would be mimicked by the earliest of their European counterparts.

The Balance Assembly

- Escape Wheel - meshes with the 4th wheel and pallet

- Pallet Fork - receives impulse from the roller jewel

- Balance Wheel - oscillates to control accuracy

- Hairspring - sets the oscillation of the balance wheel

- Balance Staff - the pivoted axle of the balance wheel

- Collet - attaches the hairspring to the balance staff

- Hairspring Stud - anchors the tail of the hairspring

- Weights - controls the rate and positional accuracy

The Anchor Escapement

- Roller Jewel - provides the impulse to the pallet fork

- Pallet Cup - meshes with the roller jewel

- Pallet Fork - holds the stones, pallet staff and guide pin

- Exit Stone - temporarily locks the escape wheel

- Roller Table(s) - mounts the roller jewel and meshes with the guide pin

- Guide Pin - keeps the pallet and roller jewel aligned

- Banking Pins - limits the travel of the pallet arm

- Entry Stone - temporarily locks the escape wheel

- Escape Wheel - meshes with the 4th wheel and pallet

Balance Wheels

The Heart of a Watch

All watches from the railroad era used a balance wheel as a means of achieving accuracy, and when paired with the escapement, let down the mainspring at a controlled rate. The earliest balance wheels were solid metal, while later models had expansion cuts to adapt for temperature changes and carried many pairs of weights around the rim of the wheel that added mass. Its steady beat was controlled by an oscillating hairspring, and most brands had some kind of regulator for fine adjustments that slightly increased or reduced the working length of the hairspring to adjust the rate.

Mean-Time Screws

These paired screws were used to make bulk timing changes by turning them in or out slightly. They were usually found near the balance wheel arms and were made with a special interference thread to prevent them from turning without force. Any company that failed to install them on their watches invited a century of hacks to molest the other weights to make timing changes.

Ruining the Accuracy

When a watch inevitably slowed from thickening oils and had no mean-time screws to make adjustments, the lazy choice was to simply grind off the balance weights to gain time. At some later point the watch was cleaned properly, which then ran too fast because of the missing weight, so washers had to be added to increase mass - all of which ruined the positional accuracy.

Hairsprings

Flat

The hairspring is the balance wheel's rebound mechanism, oscillating in and out five times every second. The coils of a flat spring all lay on the same plane, anchored at either end. At the center is the collet, a brass split-ring that grips the balance staff, and at the tail is the stud, produced in many different styles.

Breguet

Prussian watchmaker Abraham Breguet is credited for inventing the overcoil hairspring, which put the final turn of the hairspring above all the other coils. While a flat hairspring applies lateral friction to the balance staff when it oscillates, the overcoil minimizes this effect by moving a much smaller distance.

Roller Tables

Single Roller

Any anchor or lever escapement requires a roller jewel, which is mounted in the roller table. On every cycle of the balance wheel this jewel gives an impulse to the pallet fork via the cup at the end of the pallet arm. A guide pin behind the cup prevented the pallet fork from drifting too early by meshing with a crescent-shaped cutout milled in the edge of the roller table.

Double Roller

Overbanking occurs when the roller jewel becomes misaligned with the pallet cup, which was possible with the single roller design. The double roller was developed to address this, using a smaller lower table with an indent to mesh with a horizontal guard pin. This allowed the pallet arm to swing only when the roller jewel was in the cup, virtually eliminating overbanking.

Types of Escapements

Cylinder

Lever/Anchor

Cylinder

A Swiss design that allowed the escape wheel to rotate via the hollow pallet staff. They were metal-on-metal and wore quickly.

Duplex

Lever/Anchor

Cylinder

A dual lock-and-drop, meaning that both pallet keys had to allow the escape wheel to rotate. Sometimes found on Fasoldts.

Lever/Anchor

Lever/Anchor

Lever/Anchor

This was the overwhelming choice for nearly all American models. It was self-starting and almost entirely friction-free.

Verge

Verge

Lever/Anchor

The earliest form of escapement. The paddles on the balance staff allowed the crown wheel to rotate, but it was also metal-on-metal.

Worm

Verge

Worm

A design patented by the New York Standard Company. The worm gear was not necessary, since it also used a pallet and escape wheel.

Mainsprings and Barrels

T-End Mainsprings

T-End Mainsprings

T-End Mainsprings

By far the most common.

Hook Mainsprings

T-End Mainsprings

T-End Mainsprings

Used in barrels with internal hooks.

Brace Mainsprings

T-End Mainsprings

Used inside slotted barrels.

Going Barrels

Hanging Barrels

GOOD

A watch barrel contains the mainspring, and a going barrel has a cover that snaps on tightly, leaving a very confined space for the mainspring to uncoil. Newer alloy springs have sharp edges that will snag on any ridges or serial numbers stamped inside this type of barrel, making for an occasionally erratic letdown. This is by far the most common design, using a slotted or T-end spring.

Hanging Barrels

Hanging Barrels

Hanging Barrels

BETTER

A hanging barrel consists of a barrel and cover that never touch each other, rotating on a common arbor and giving the spring more room. Waltham used this design on several of their models. The mainspring is allowed to unspool at a much smoother rate, producing more consistent torque.

Hanging barrels have an internal hook to anchor the mainspring.

Motor Barrels

Hanging Barrels

Hanging Barrels

BEST

A motor barrel has a pair of internal jewels between the winding arbor and the barrel and its cover. This increases accuracy by letting the mainspring unspool without friction, and when used with a hanging barrel makes for the smoothest letdown.

External jewels on the plate are entirely for show and to inflate the count, and do not reduce friction or improve accuracy.

All About Stopworks

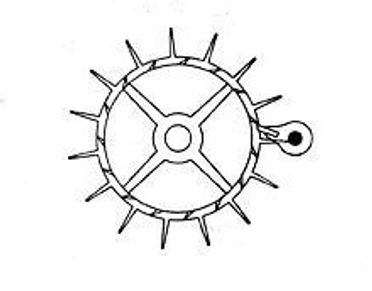

The Geneva Cross

The stopworks, or Maltese Cross, originated in Switzerland in the 1700s as a means of limiting mainspring travel in watches. A single-tooth drive cam was mounted on the barrel arbor, which mated with a driven wheel that had several open spokes and a single closed one. After a given number of rotations the closed spoke would lock the drive cam and prevent the mainspring from turning.

Most stopworks have been tossed by lazy hacks as unnecessary.

Achieving Isochronism

The intent of stopworks was isochronism, the ability of a watch to run at the same rate despite any changes in its power source. The red line in this graph shows the drive torque of a mainspring, and the stopworks allowed the movement to run only in the middle two-thirds of its linear force, where its power was most consistent. While the accuracy may have been slightly improved, stopworks also reduced the run time on a 40-hour spring from roughly 35 hours in real time down to 24 hours.

Railroad Standards

What Made A Watch Railroad Grade

Our growing country moved nearly everything by rail in the 1880s, so an accurate timetable between freights became increasingly important. For decades the railroad companies had generally accepted any 18-size 15-jewel watch for service, but in 1891 the Kipton, Ohio crash killed several people because an engineer's watch had stopped, and the rules changed. Webster C Ball, a successful jeweler and store owner, was given authority as Chief Time Inspector, overseeing thousands of miles of track. New standards were adopted, and by the turn of the century a Railroad Grade watch was American-made, open-face, lever-set, either 16 or 18-size, had a minimum of 17 jewels and was adjusted for temperature and positions. It had to be equipped with a steel escape wheel, a micro-regulator, and a bold Arabic dial. Railroad workers were required to submit their watches for regular inspection, and the most important criteria was that any watch had to be accurate to within 30 seconds a week.

Positions

A watch can be oriented pendant up or down, pendant left or right, or dial up or down. There are nine total adjustments - the six positional ones, isochronism, plus one each for heat and cold. When a movement was marked with a given number of positions it meant certain orientations, although this was not universal, and isochronism and temperature corrections were supposed to be included. Some factories milled the word "Adjusted" on the plates with no explanation, while other firms inscribed the total number of adjustments to which the watch was timed against.

Accuracy

Accuracy was the most important aspect of any watch, so high-grade movements were adjusted to keep better time. These adjustments offset the effects of friction, gravity, temperature, and the fading torque in a spent mainspring by fine-tuning the balance, and getting a watch to run accurately took hours of work by a skilled watchmaker.

Movement Sizes

American watches used the Lancashire gauge, which is based on the dial plate of a O-size watch measuring precisely a standard inch in diameter as a starting point, with each ascending size adding exactly 1/30th of an inch. The additional 5/30 inches was for the mounting shoulder up to a 16-size watch, when the diameter was increased to 6/30 inches.

Different countries had their own system, adding to the confusion. The two most common sizes - 16 and 18 - have been highlighted in yellow on this chart and is downloadable in .pdf by clicking the button below.

Plate Layouts

Full Plate

Bridge Plate

Full Plate

All American companies offered full plate designs, with the balance wheel being the only visual component of the gear train. The balance wheel was recessed on some models, but was always located above the upper plate.

3/4 Plate

Bridge Plate

Full Plate

A 3/4-plate design protected the balance wheel between the plates. Some models split the plate between the mainspring (barrel) bridge and the gear train bridge, while others had a single plate to cover both areas.

Bridge Plate

Bridge Plate

Bridge Plate

A bridge movement also stacked the balance wheel inside the gear train, with as many as four separate upper plate bridges. A "false" bridge model was actually a single piece with shallow milling cuts to mimic the real thing.

Plate Finishes

Gilt (Gilded)

Gilt (Gilded)

Gilt (Gilded)

Gilded plates were the most common prior to 1880, chemically transferring a thin layer of gold onto bronze plates.

Nickel

Gilt (Gilded)

Gilt (Gilded)

Nickel-plated bronze was an ideal choice into which dazzling patterns could be milled or turned, called damaskeening.

Two-Tone

Gilt (Gilded)

Flashed Gilt

Two-toning required the initial step of masking of areas of the plates with wax and then gilding to achieve this look.

Flashed Gilt

Flashed Gilt

Flashed Gilt

This effect was similar to two-toning, except the patterns were milled before the plates were gilded.

Frosted

Flashed Gilt

Acid-Etched

American Waltham pioneered this look, with the patterns milled after sand or bead-blasting the plates.

Acid-Etched

Flashed Gilt

Acid-Etched

US Watch of Waltham was the first factory to etch a pattern with acid on mirror-smooth plates.

Watch Lanyards

Tired of your watch smashing to the floor and having to pay all those irritating repair bills?